Pézenas

Photo: Marylou Hillberg

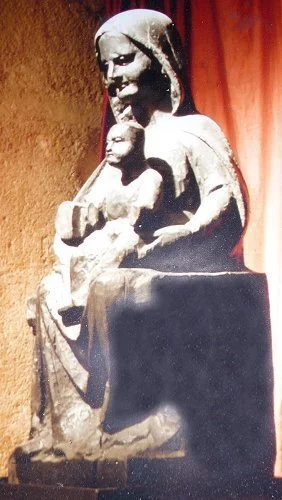

Our Lady the Black One

(Notre-Dame la Noire)

The Virgin of Bethlehem

(la Vierge de Bethléem)

Pézenas is in the Hérault department of the Languedoc-Rousillion region. The original is in the treasury/museum behind Collegiale Saint Jean's church at the Place du Marché, usually open daily 3-6 p.m. The copy that is venerated as the presence of Notre-Dame la Noire is in Sainte Ursule's church in the Rue Henri Reboul, open only during mass on Fridays at 9 a.m., 12th century or older, darkened cedar wood/painted wood, 60 cm.

Tradition says that Our Black Lady washed ashore somewhere in France where a sailor from Pézenas found her and brought her to his home town. However, an 18th century manuscript written by a certain Officer Poncet claims that a Commander of the Pézenas chapter of the Knights of St. John brought two Black Madonnas back from a Crusade. Presumably he “found” them together on the island of Rhodes. The Knights of St John are also known as the Hospitallers or the Knights of Malta. When the Knights Templar were eradicated in 1312, much of their property went to the Hospitallers who had many parallel characteristics. Since their first military action on Rhodes ended in 1310, one can conjecture that the statue is at least from the 12th century. Since the knight who brought her to Frnace was originally from Toulouse, he gave one of the statues to the church of La Daurade in Toulouse and the other to his order’s church in Pézenas (Saint Jean de Jérusalem’s)

Ean Begg states that Napoleon III “dedicated a (perpetual) lamp in her shrine to gain her support for his army (…) against the Turks in 1860.”¹ However long before him, the people of Pézenas already set up a perpetual lamp for their black Mother and had this important act of recognizing her divinity notarized on May 18th 1340. So we know her cult to be at least that old. (For more on perpetual lamps dedicated to Mary read in the introduction under the sub-heading “Christian and non-Christian Feminist views”.)

The original in the museum

The one in Sainte Ursule. Photo: Lena Robinson

In 1412 the Confraternity of Our Lady was founded. Confraternities are usually all male affairs and serve to foster a particular devotion. In 1694 a women’s Confraternity of Our Lady of Bethlehem was established in the Ursuline convent, under the auspices of their priest of course. Both organizations shared the same intention of ensuring honor and devotion to the Black Madonna of Pézenas. They would organize great processions on annual feast days and also during times of special needs, e.g. during severe droughts, floods, or epidemics. Countless miracles are attributed to this Madonna, especially during the course of such processions, where the whole town would pour into the streets: simple lay people and aristocrats, monks and nuns, high ranking clergy and secular authorities. Poncet, the author of her annals, says about one such procession held as an urgent plea for rain: “I remember seeing with my own eyes that the rain sometimes didn’t even wait to fall till the image had been returned to its church.”²

During the Revolution the statue escaped destruction, but not without a scratch. Mary lost her right hand and both feet; Jesus was scalped and also lost his right hand. The church of the Maltese order, which she had inhabited, was destroyed and Our Lady left among the ruins. Taking her life into her hands, Madame Vidal, a pious woman, asked a revolutionary if she could take “that worm eaten piece of wood as a toy for my grandkids”. When he agreed, she hid the statue under her smock and brought her to the priest who was at the head of the women’s confraternity headquartered at the Ursuline convent. After the Revolution, when the convent church doubled as a parish church, it was decided to keep it as the permanent home of Our Black Lady.

Notice her smile. Not many Black Madonnas smile. Supposedly she wears an Egyptian hairdo under her veil.

Footnotes:

1. Ean Begg, The Cult of the Black Virgin, Penguin Books, London: 1985 p. 211

2. When I visited the Black Madonna of Pézenas in 2009 a little, old church lady took me to her front door and let me wait outside while she went up to her apartment and copied two chapters of a book on her home town for me. I didn’t dare send her back upstairs to get me the name of the author and the book. All I can tell you is that the chapters are called “La Vierge Noire” and “Une Ville d’États”. Unless otherwise marked, all information in this entry comes from the chapter “La Vierge Noire”. This quote is on p.85