Mayres

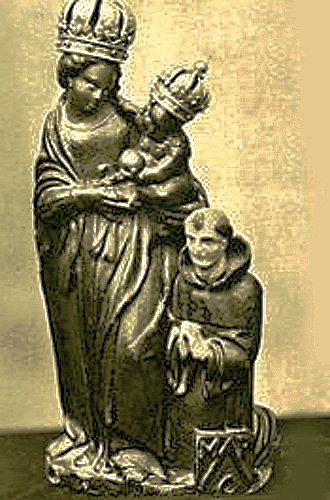

Notre-Dame-de-la-Roche (Our Lady of the Rock),

Our Lady of the Side-Eye, Black Madonna of Mayres

Original statue now stands behind the altar in the village church of Mayres, department Puy-de-Dome, about 1.15 hours from Clermont-Ferrand. She used to dwell in a chapel in a field at end of the woods South of Mayres where they keep a copy of her, 14 C, stone, small, very black and shiny. Ask in town if the chapel is open before you go up there. Painting by Afro-Filipino artist Laylie Frazier’s of “Our Lady of the Side-Eye”

The Black feminist scholar and activist Dr. Christena Cleveland discovered this previously rather unknown Black Madonna and dubbed her Our Lady of the Side-Eye. She comments: “Our Lady of the Side-Eye has no problem proclaiming that She is absolutely petty and will put a White man in Her statue just so She can tell the world how much She’s not here for him.”[i] Really?! I agree that her facial expression is unique and she does seem to be rolling her eyes at the monk kneeling at her feet. But if we consider that according to the University of Dayton “the statue commemorates the vision of a 12 C monk”, doesn’t it seem unlikely that she would disrespect the monk to whom she appeared? Her face is turned towards the monk. Could this just be a bad photo, copied from the 1936 book it came from? If anybody goes to Mayres and could get the world a better picture, it would be greatly appreciated. I like Laylie Frazier’s rendition, where it’s more clear that the monk looks up to Heaven and maybe so does the Black Madonna. Maybe the artist wanted to portray her as simultaneously turned towards the monk and towards Heaven and it ended up looking like rolling eyes.

In the paragraph following her statement about Our Lady of the Side-Eye being righteously petty, i.e. narrowly interested and sympathetic only towards Black women, Cleveland nonetheless describes her as “a Black woman who cares deeply about the flourishing of all humans” but calls White people to do better. That sounds a lot better.

When I wonder what the Mother of God may be thinking or feeling, I check not only my own intuition, which is all too likely colored by my own feelings and preconceived notions but also the messages she gives in her apparitions in Medjugorje. Does she ask us to do better? Absolutely. Does she single out any particular group as doing especially poorly while another needs no improvement? No, unless it’s in the most general way, like “those who chose death and hatred”. Her guidance towards betterments are always addressed to all of humanity. Is there really anybody the Madonna, no matter what color, is not here for? Does she pick sides? No! In the middle of the Jugoslavian civil war, she proclaimed: “Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics … you are all my children… All humans are equal before God….”

According to the local newspaper, Our Lady of the Rock used to draw a bigger crowd up the mountain on her feast day, but it’s still a good number of devotees. photo: Martin Christiane

Certainly, one can’t deny that Black Madonnas touch the hearts of Black women in a special and particular way. And yes, one function of the Dark Mother is to make her dark skinned children feel welcomed, included, empowered, freed from oppression. Yes, her legends tell of the dark divine feminine insisting on her will and resisting the plans of male clergy, but that doesn’t mean she’s not here for them as well. She wants to convert, not exclude. Does she get frustrated with humans? Anguished certainly. There are many stories about the Madonna crying over our sins in her apparitions and also statues and icons weeping, but none about her rolling her eyes or excluding anyone from her love, compassion, and concern.

This Black Madonna was stolen at end of the 18th century, but when she brought misfortune on the family of the thieves, they hid her in a cleft rock where she was later found. She was saved during the Revolution by a pious women. She is celebrated on the first Sunday following September 8th, the traditional birthday of the Virgin Mary.

Footnote:

[i] Christena Cleveland, PhD, “God is a Black Woman”, Harper Collins Publishers, New York: 2022, p. 228